This blog is about a well-known business concept called the Service Recovery Paradox (SRP).

What’s SRP? It’s a pretty simple theory. A good recovery following a service failure can turn angry, frustrated customers into loyal ones. Service managers have known about this paradox for years.

The concept was first discussed in a popular Harvard Business Review article as far back as 1990. The authors – Christopher Hart, James Heskett and Earl Sasser – are all extremely well-respected academics and business practitioners.

But are they right? Let’s take a closer look.

Service Recovery at Slack

Why don’t we start with an example.

Ever heard of the American tech company Slack? Several years ago, Slack had a major service failure:

Tuesday, November 23, 2015 started out like any other day at work for James Crenson. Coffee, check email, prep documents for weekly meeting, solicit input from co-workers on slack. Um, Slack?

Outage

At 8:50am, popular workplace messaging service Slack suffered a massive outage, leaving over a million users around the world unable to send or receive messages and files for almost three hours in the middle of the workday. Angry users took to twitter and other social messaging sites to complain about the inconvenience. The situation had the potential to explode, but Slack was ready.

The team messaging tool had a solid plan in place for mass outages. A well-coordinated group effort handled support issues including a comprehensive social media blitz to contain the negative customer experience (CX). Over the few hours that the service was down, the official @SlackHQ account tweeted over 2,300 times with humorous, thoughtful, and most importantly, personalized – responses to customers complaining about the service outage.

Response

Not only did the all-out response wow users, but @SlackHQ gained over 3,300 followers – 7x more than average – on a day that could have gone down as the worst in company history. Slack was able to quickly contain the damage, took complete responsibility, kept its customers well informed and handled a stressful situation with humor and efficiency.

Throughout this process, Slack deepened the trust of existing customers by demonstrating that the company was prepared in times of crisis. Its expert handling of a negative situation enhanced its relationships with existing customers, boosted the brand’s reputation and even served as a springboard for an expanded customer base.

This is an exceptional demonstration of the value of the phenomena known as the “service recovery paradox.”

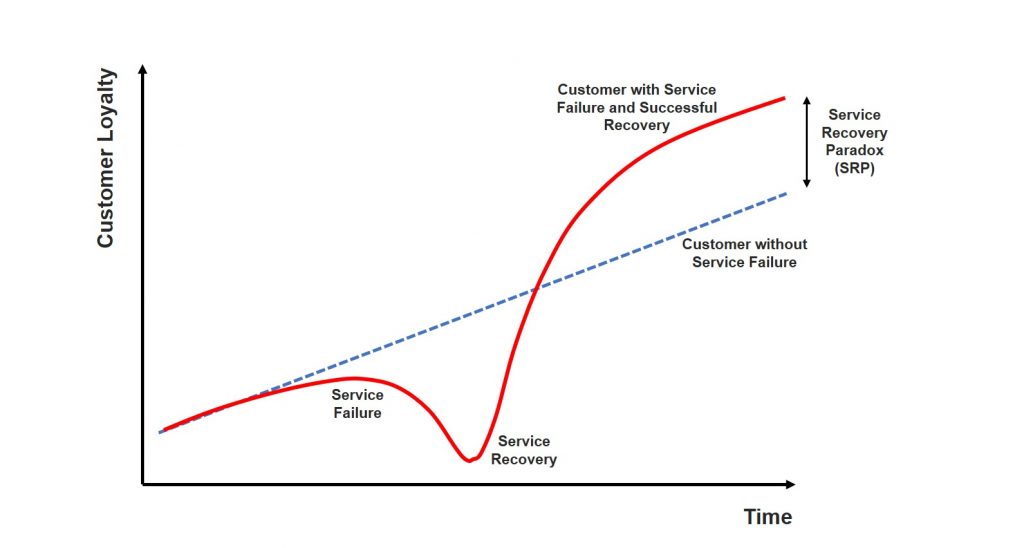

The graphic below explains the Service Recovery Paradox.

Loyalty generally increases over time when service is delivered consistently well. It falls rapidly if there is a service failure but loyalty increases again when service is restored and the service recovery is handled well. In fact, loyalty becomes greater than if no failure had occurred in the first place. That’s the paradox.

Fact or Myth?

The Service Recovery Paradox is generally accepted as fact. But where is the evidence for it?

Some years ago, Celso Matos decided to find out. He and a couple of colleagues from the Federal University of Rio Grande do Sul in Brazil conducted a ‘meta-analysis’ of all academic articles that discussed SRP. In total, they found 24 documented examples of recoveries following service failures. 19 of the 24 examined the impact of service recovery on satisfaction; 12 examined the impact on repurchase intentions; six looked at word of mouth (advocacy).

Their results were very interesting and not encouraging for companies with a poor service ethos.

Matos concluded that “satisfaction increases after a high service-recovery effort” but that “repurchase intentions are not increased by a high service-recovery performance.”

Service Recovery does NOT lead to greater loyalty

Matos and his colleagues explain that “customers are willing to make a positive evaluation of a firm providing a high recovery effort, but they are not likely to repatronize this firm”. They go on try to explain why this might be the case.

One explanation is that satisfied customers are not necessarily loyal. We know this from our own analysis at Deep-Insight. Another explanation is that people will give you a lot of credit for pulling out all the stops to recover a bad situation after a bad service failure. However, they will still doubt your ability to ensure no similar service failures occurs again. That’s pretty important when your 12-month or 10-year contract is coming up for renewal. They might give you good customer satisfaction (CSat) scores, but will they sign up for another contract?

In general, satisfaction levels do recover if a Service Improvement Plan (SIP) is put in place but loyalty does not. This does not mean the Slack example discussed above is not true. It just means that you need to go to extraordinary lengths to win back the trust and loyalty of clients when they experience a service failure.

The Relationship between Service and Trust

Some years ago I wrote a blog called Trusted Relationships = Consistently Good Service. It was based on our analysis of tens of thousands of customer feedback results from Deep-Insight’s database gathered over a period of 15 years. The analysis showed that of all the elements in our Customer Relationship Quality (CRQ™) methodology, Service Performance was most strongly correlated with Trust.

It stands to reason, if you think about it. What happens when you deliver a consistently good service to a client? Their levels of trust in you and commitment to your company increase. Fail to deliver the service consistently, and their trust erodes quickly. Consistently fail to deliver, and both trust and commitment levels can disappear completely. Trust and commitment also take a very long time to rebuild.

‘Quality is Free’ so make sure to get it ‘Right First Time’

There’s a really important lesson here. Service failures are the sworn enemies of long-term profitable relationships. That’s why it’s worth investing time and effort to minimise the chances of a service failure ever happening in the first place. You may never succeed completely but it will be worth the investment. In fact, it won’t cost you anything.

This is where the old Total Quality Management (TQM) principles come into play. In 1979, Philip Crosby wrote a seminar book called Quality Is Free. His basis message was that it costs absolutely nothing to build quality into products and services. If anything, you’ll make money by reducing the cost of re-work and failed business relationships.

Quality really is free, so if you’re in the service business, make sure to get it right first time.

If you operate in the B2B world, ask yourself the question: “Is CSat the right thing to be measuring in the first place?” Maybe you should be measuring something different.

UPDATE: 27 APRIL 2023

We have just written a follow-on article on the Service Recovery Paradox in B2B companies. Click here to read.